Silk worm is a moth

My foolish ignorance and poignant realization.

I recently came across an interesting podcast on butterflies vs. moths, where one of the invited speakers, while discussing moths and their biology, mentioned in passing that the silkworm is a type of moth. This might be common knowledge for many, but I was a bit taken aback, because for me, the silk worm was always some type of worm. My past visit(s) to a silk farm flashed before my eyes, where I had seen them as worms grown for extracting silk. Being the nature enthusiast I am—generally fond of flora and fauna—I was surprised that this simple fact eluded me. This nagged me for a while until I questioned my own ignorance—where it stemmed from and why. Upon some reflection, I believe it came from the following reasons.

First, silk worms look like worms— these squiggly, legless invertebrates with soft bodies that crawl around. “Worms” is an umbrella term for various groups of beings exhibiting these characteristics. I also knew that silkworms are insects, but I never asked myself if they are also worms, which begs the question: are all worms insects? Clearly not. For one, I knew that the earthworms and tapeworms are not insects. In fact, they belong to an entirely different group of invertebrates called Annelids. Then, what defines a worm?

Worms, in a broader definition, consist of animals with soft, slender, and segmented bodies. One of their defining features is that they lack appendages (legs). They mainly belong to the phyla1 of Annelida, Nematoda, and Platyhelminthes. Some examples of worms include earthworms, roundworms, and flatworms.

In contrast, insects have six legs, three main body sections, and an exoskeleton that provides support for their internal organs. Additionally, the majority of them also have wings2. All insects belong to a different phylum than the worms we saw before, called Arthropoda. Moths are a group of insects (and hence arthropods) that belong to the order Lepidoptera. They are in the same order as butterflies, but are less flashy-looking. In fact, butterflies are a subgroup of moths.

Silk worms are a type of moth, and hence an insect. But then, why do we call a “silk worm”, which is technically an insect, a “worm”?

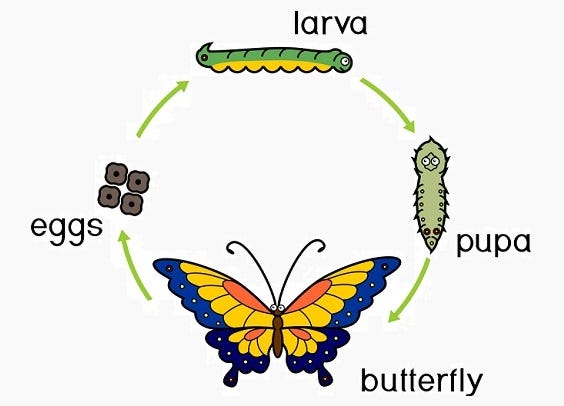

To understand this, we must first understand the lifecycle of an insect. The lifecycle of insects can be categorized into two types: complete metamorphosis and incomplete metamorphosis. Moths undergo complete metamorphosis; therefore, I will only discuss this aspect here. A moth which undergoes complete metamorphosis consists of 4 stages in its lifecycle: egg, larva, pupa, and adult3.

The stage of interest here is the larval stage, when a moth egg turns into a caterpillar—a squiggly, slender-looking animal. And doesn't it look like a worm! What we see in silk farms are indeed the caterpillar versions of the silk moth, and hence the name silk worm. Only because the silk caterpillar resembles a worm, it’s a common misconception to name (and also consider) them as worms, when indeed they are insects.

I started this post with confusion I had about whether silk worms are worms or moths. Why did I go through the pain to explain the difference between a worm and a stage in an insect's lifecycle resembling a worm, you may ask. Perhaps because it was important for me to understand this distinction and not mistake one with the other again.

This may sound trivial, but it was clearly a poignant realization for me. The second reason for my ignorance was that, as a child who lived in a region famous for producing a popular type of silk in India, I had visited silk farms and seen these silkworms. I had seen the worms feed on mulberry leaves and intricately build a cocoon (the third stage of their lifecycle, the pupa) around themselves. What I did not get to see was the last stage in the insect’s lifecycle—the adult moth—where the winged moth breaks out of the cocoon.

The silk farms often don't show us the adult moth because they are killed in the pupal stage to extract the silk, even before they reach the adult stage4. The silk strands are extracted from the white cocoons that the larva builds around itself using its own saliva. Often, one cocoon is built with a single strand of protein from the saliva that is long enough to form a cocoon. If the pupa is allowed to surpass this stage—to break open from the cocoon and emerge as a winged insect—it breaks these intricately woven strands, resulting in not-so-viable silk. For this reason, the cocoons are boiled in water, thereby avoiding damage to the silk strands, which makes it easier to extract full-length strands after, ultimately killing the insect.

Humans have been farming silk for more than 5,000 years, since its cultivation began in China. Over these years, we have domesticated these moths to produce high-quality silk and discarded the populations of moths that were not otherwise valuable. These domesticated species, known as Bombyx mori, have now reached a stage where they can consume a large amount of mulberry leaves and grow to enormous sizes as caterpillars, build larger cocoons, and produce more high-quality silk. This has resulted in the adult moth being unable to fly and survive on its own. It completely relies on humans for further breeding and progeny. Furthermore, we cannot extract silk from any of the wild species of silk moths. We only have one species, and boy, doesn't it look exotic!

I do not want to delve into the ethics of silk farming (technically known as Sericulture) here, but I would like to instead address my obliviousness to the apparent beauty that nature possesses. How was I so blind to nature's affairs? But then I asked myself, was I blind or blinded by what was beyond what I saw at the silk farms? It bothers me that modern humans in the industrialized world, whether through farming practices or consumerism in general, are so far removed from the complexities and manner of production of goods that we forget we eventually extract them from nature. As a consequence, we tend to consider nature and other beings in isolation from us, when in truth, we are just a small part of it—a part of one extraordinary whole.

Beyond our necessities, we humans have extracted from nature, only to fulfill our wants and desires, especially when some things are entirely avoidable. I do not intend to advocate solutions for these issues, but at the very least, one can question oneself and the system. For example, in the case of silk, one can raise awareness of the natural aspect of a commodity, allowing us to feel more connected to the natural world rather than detached from it. The process of learning about the lifecycle of a silk moth and worms for this post was not only educational and fun for me, but also humbling. I believe learning anything about the workings of this magnificent natural world is humbling and ennobling.

One can also question what goes into making the things we use and how they are manufactured, as well as whether what we want to consume is entirely necessary. More importantly, at what cost to the environment and its species?

Phylum (pl. Phyla) is a level of classification in the hierarchy of life below the Kingdom. In the context of this post, the Kingdom is Animalia, specifically invertebrates, which comprises several phyla.

With some exceptions, like ants, lice, silverfish, and some beetles.

Remember the biology class from high school?

I wondered, if all pupae are killed, how are the new eggs laid? Because only an adult female moth can lay eggs. It turns out that a small batch of pupae is separated, which hatch out of their cocoons and are bred to lay eggs. Since a female moth can lay hundreds of eggs at once, the farms can do away with just a small batch of adult moths, still having enough pupae to produce silk.